The year is 1924, and if you remember your world history, you’ll recall that it’s a relatively important year. The International Business Machines Corporation, the multinational technology company later known as “IBM,” is formed. Russian communist, political theorist, and revolutionary Vladimir Lenin has died and Joseph Stalin has begun to purge his rivals on his rise to power. To the west, Adolf Hitler is imprisoned in Bavaria and is devoting all of his time to writing his personal manifesto: Mein Kampf. Karl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler have formed an automobile company known as “Mercedes Benz,” and fittingly enough for the current season, the first-ever Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade is held in New York City.

Meanwhile, in France, two very important things are happening. The first Olympic Winter Games are taking place in the French Alps, marking the start of a tradition that is still held today. More important to us, however, is what is happening due north of the Olympic Games in Alsace, France. Ettore Bugatti, the Italian-born Frenchman behind the to-be world famous Bugatti name, was hard at work developing his latest car. Dubbed the Type 35, the open-wheeled racer would catapult the Bugatti name into the spotlight and become the most successful car his brand will ever see. But let’s start with the blueprints.

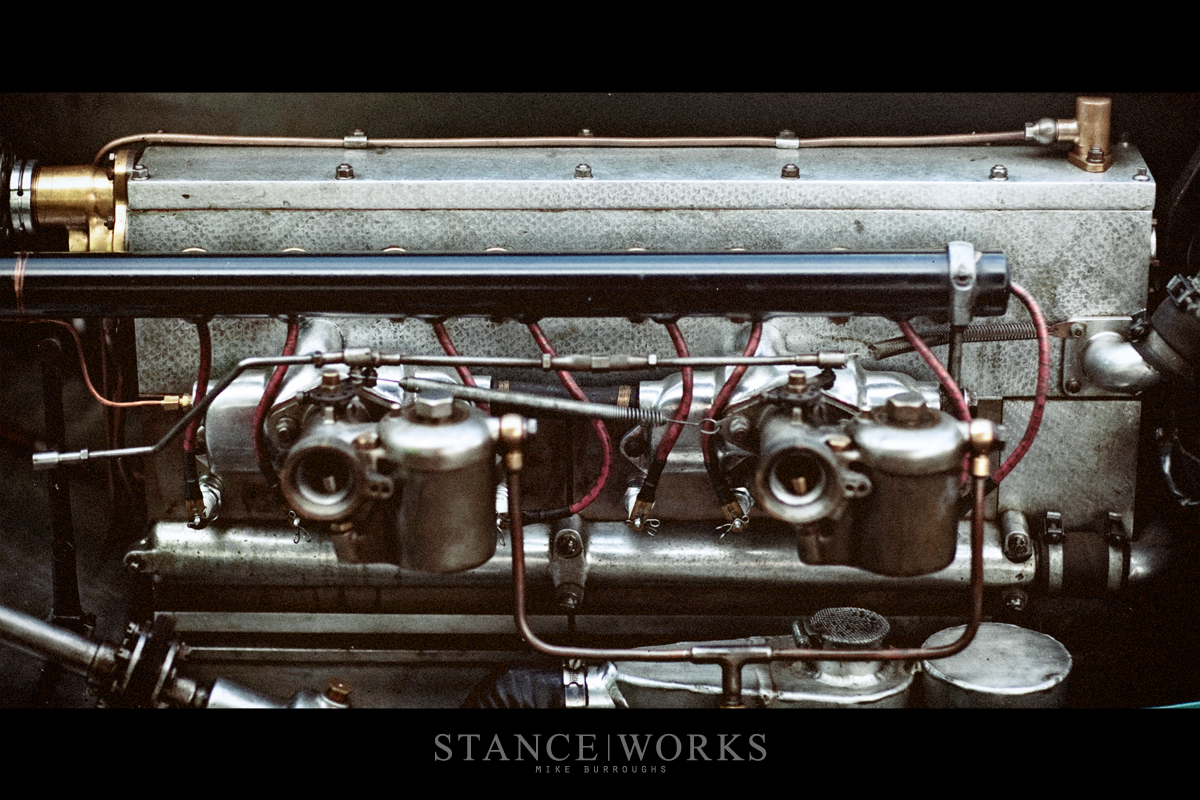

Evolved from his Type 30’s straight-eight (inline 8-cylinder) engine, Ettore stuck with his tried and true bore and stroke of 60mm and 80mm, respectively. The single overhead-cam engine utilized a ball bearing system for five main bearings which allowed the 1990cc, 3 valves-per-cylinder engine to rev to 6,000RPM. A pair of Solex carburetors fueled the engine, which remained naturally aspirated until later in production. 90 horsepower was pushed through a 4-speed manual gearbox to the extremely unique alloy wheels – the first of their kind.

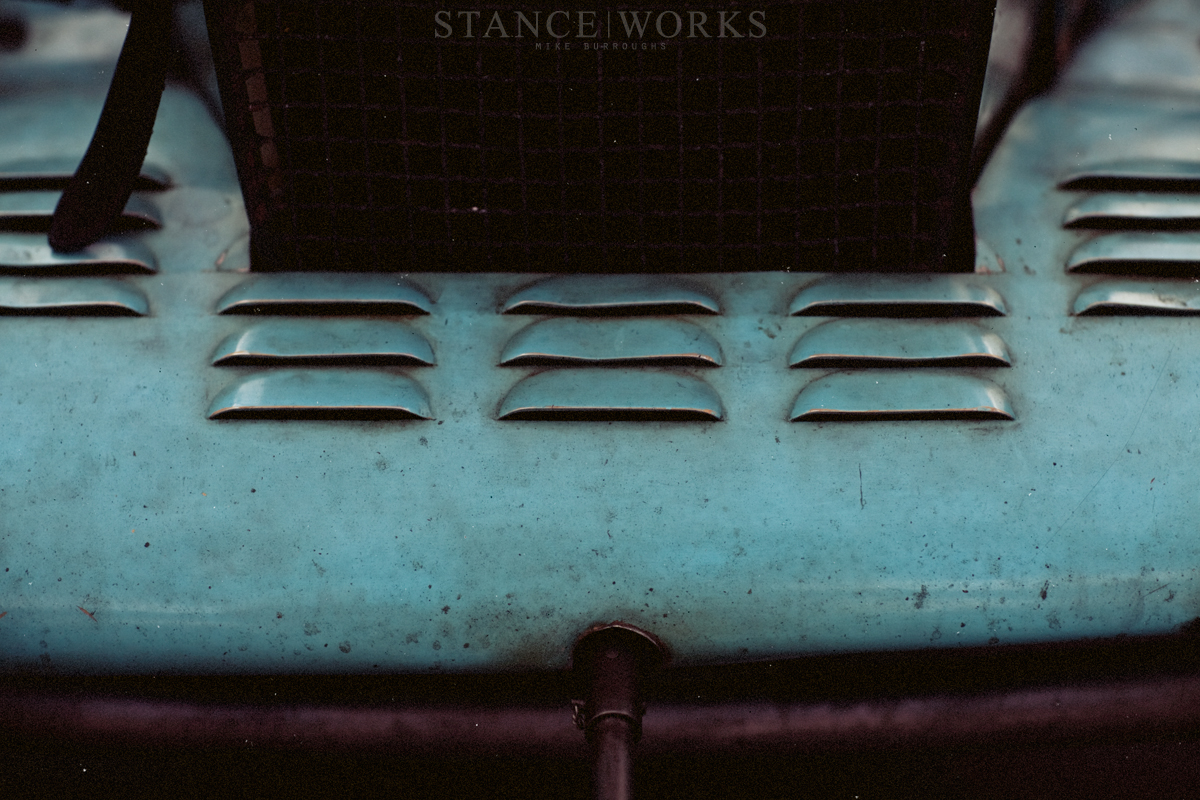

The body of the Type 35 is heralded as one of the most beautiful racers of all time. The aesthetics of the body were heavily refined in comparison to its predecessors. The Type 35’s updated horseshoe grille would become the iconic mark of the Bugatti line. Aerodynamics even came in to play; while having a drag coefficient only slightly better than a bank vault door, it was enough to be a competitive edge over Ettore’s competition. The chassis and running gear were entirely new for the 35, featuring a track width of 1200mm, and a wheelbase exactly twice as long – 2400mm.

Live axles front and rear supported the car; semi-elliptical leaf springs gave the car its world-dominating handling characteristics. A trademark design aspect to the Type 35’s suspension was the unique passing of the leaf springs through the front axle, as opposed to the typical U-bolt solution from older Bugatti models. Carrying forth with the ingenuity, the front axle was hollow to reduce unsprung weight. Finishing off the suspension, Ettore Bugatti was a brilliant man, noting that the extreme positive camber helped neutralize the car’s handling characteristics by promoting understeer in an era defined by opposite lock.

But the Type 35’s revolutionary design aspects didn’t stop there. As previously mentioned, the alloy wheels built for the 35 were something the world had never seen before. Cast in aluminum, the wheels were patented by Bugatti and featured integrated brake drums – a design feat that further reduced unsprung weight and meant that the changing of a wheel also meant new brakes, which helped tremendously during pit stops. The beautiful 8-spoke alloys have become almost as iconic to the Type 35’s aesthetic as its arched nose.

Ettore’s Type 35 finally debuted on August 23, 1924, at the Grand Prix of Lyon. A pair of 35s finished 7th and 8th, giving the winners at Alfa Romeo little to worry about. Or so they thought. Once 1925 rolled around, the automotive world was shaken by the force of Bugatti and his Type 35. While sources vary on the final tally, one thing is for sure: in its first year of racing, the Type 35 landed 501 wins and smashed nearly every record in the book. Ettore’s creation seemed unstoppable. Over the next several years, the 35 would go on to win thousands of races. In 1926, the Type 35 took home 12 major Grand Prix victories and stole the Gran Prix World Championship, but Bugatti’s reign was only beginning.

The Targa Florio, a Sicilian open-road endurance race, is one of the oldest racing events in the world. Founded in 1906 and raced regularly until the late 1970s, the circuit quickly grew to become one of Europe’s most important races. In 1924, the 24 Hours of Le Mans was only on its second year, giving the Targa Florio clout as the race of the time. In 1925, Bugatti entered their Type 35 into the competition. Our boys in blue took home a first place finish with an overall time of 7 hours, 32 minutes, and 27 seconds. They returned the following year and saw repeat success. This continued for Bugatti and the Type 35 for five consecutive years, a feat that seals the Type 35 into the automobile hall of fame.

The inaugural Monaco Grand Prix took place in 1929, and has since become one of most prestigious races in the world, along side the 24 Hours of Le Mans and the Indianapolis 500, which form the Triple Crown of Motorsport. Having run nearly the same 2-mile course since its inception, the tight, tangled, and frantic track is now part of the Formula One World Championship series. It is renowned for its technicality, its narrow streets, tight turns, elevation changes, and the inclusion of a tunnel. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that the Type 35 holds the first-ever win at the world-famous circuit. Bugatti went on to take the win in 1930, 1931, and 1933.

It should be noted that all of these victories were amassed by a relatively small number of cars: only some 300 Bugatti Type 35s were built, including all of the variations such as the 35A, 35C, 35T, and the final 35B, which won the 1929 French Grand Prix (of course). But for the original Type 35, just 96 models were built, and that brings us to the car in front of us. One of 96 – relatively small in the scope of things: 87 years later, it still stands tall amongst the rest of the titans of motorsport. This particular car belongs to Nathanael Greene, and I couldn’t help but stop and stare when I crossed its path.

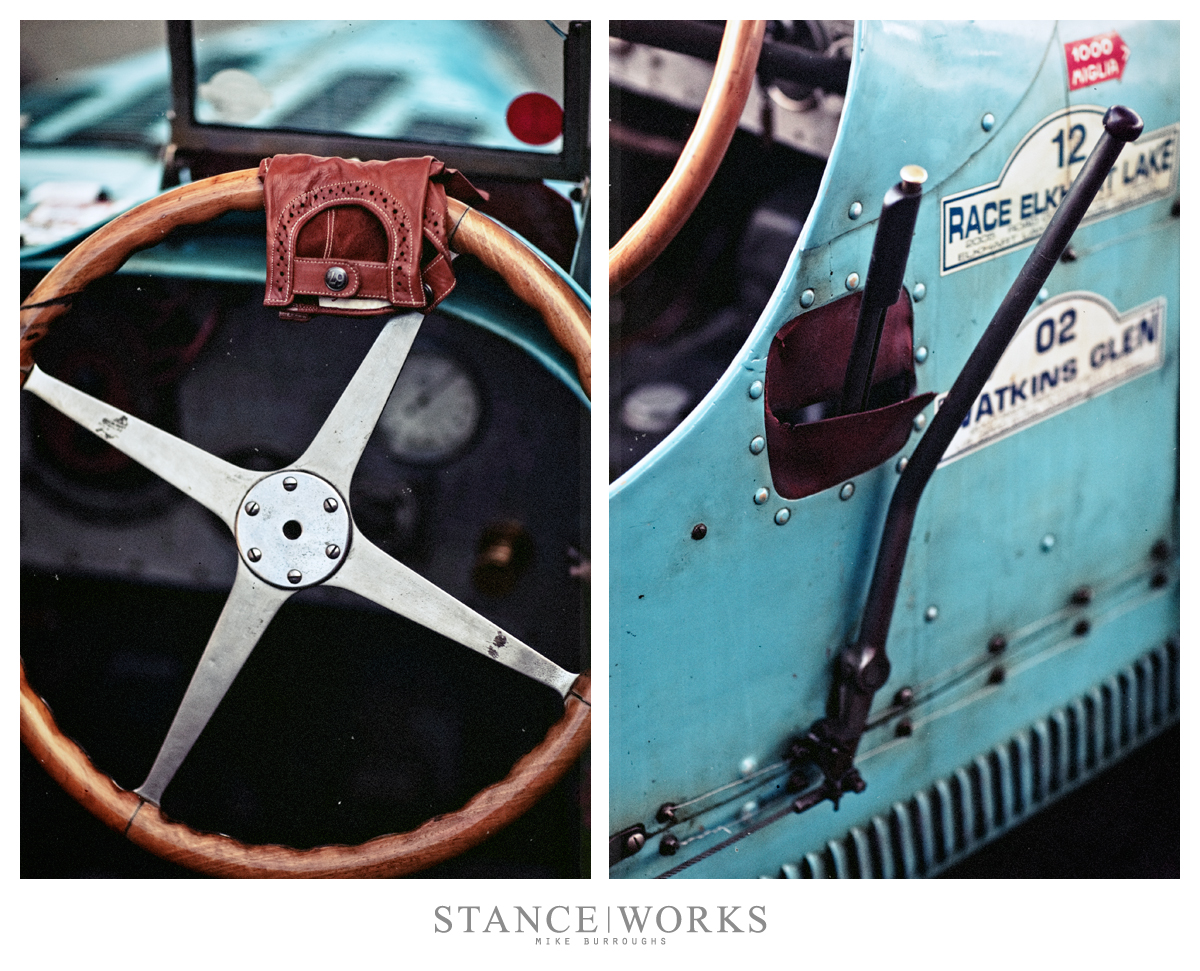

There was something immediately special about Nathanael’s car to me; I knew nothing about it, however, it stood out against the six other 35s at the Rolex Monterey Motorsport Reunion. Each car present was a distinct and familiar hue of blue, deep yet subtle, and truly fitting for the body of the 35. Yet Nathanael’s car didn’t match. Wrought with age and patina, the sky blue paint on his car had a dull sheen beneath the grit, grime, and the hard-earned wear and tear. Amongst cars that pride themselves on showroom-level preservation and Councours-level restoration, Nathanael’s car sits unrestored, wearing its age with honor.

There was something simply special about this car – it stopped me in my tracks like few cars ever have. I found myself abandoning the race I was there to shoot; instead I wanted to study and admire a machine that has aged perfectly. The flawless lines of the nearly one-century-old racer are outlined like wrinkles on a veteran’s face. Each nut and bolt, safety wired to the next, surrounded by oxidization, oil, and maybe even a tinge of rust, scream from dozens of yards away that this is a true race car. This is automotive history at its finest. Few cars have spoken to me in a way this one has, and thus I share it with you. Perhaps you’ll feel the same.